http://www.hrichina.org/crf/article/5512

Hua Ze

The Kidnapping

I have stayed in Northeast China for two weeks, filming during the daytime, and surfing the Internet at night. I know that after Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Prize, Beijing became very tense. After consulting with Teng Biao,1 I decided to stay in his office in Wangjing, a suburb outside Beijing, for a while and return to Beijing after it recovers from the madness.

On October 27, 2010, I board my flight around noon and turn off my mobile phone so that my location cannot be tracked. I take out the battery and SIM card, breaking off communications with others.

Around 3:00 p.m., I land at Beijing Airport, say goodbye to Teng Biao and others, and take the airport shuttle bus to Wangjing with his assistant, Huanhuan. On the highway, I realize my notebook computer is missing. My damned memory! I must have left it on the plane.

Upon arriving at Teng Biao’s office, I put down my luggage and use a landline to contact the “lost and found” office at the airport. I am told that they have information on my computer in their database. I immediately go to the College of Administration for Civil Aviation Officials, a block away, to take the shuttle bus to the airport.

As I approach the college gates, someone grabs me from behind and drags me backwards, face up, as a black hood comes down from above. My first thought is that the black hood is thick and stinks of feet.

“Help!” I hear myself cry and struggle desperately, hoping that I can hold on until the people who witness the kidnapping can report it to the police. During the struggle, the black hood falls off. As seven to eight strongmen are stuffing me head down and feet up into a white minivan, I resist by hooking my feet to the door frame, while a kidnapper’s distorted face stares down ferociously and says: “If you go on resisting, you will die!” A moment later, I lose consciousness.

When I wake up, I feel the minivan stop and think we have arrived at the destination. Soon the minivan starts to move again, and stop again. After several rounds of stopping and going, it speeds up. I realize that we were waiting at traffic lights, and now we are on a highway heading to the suburbs.

I don’t how long afterwards; cold water hits me in the face. In a daze, I see a dark room, with one light, aimed directly at my face. Many faces are swaying in front of me. A hand reaches out, grabs my collar, yanks me up from the ground, and throws me onto a stool. My head hits the wall hard. I taste blood, and my chest hurts. It reminds me of the “Garbage Cave” from the novel The Red Rock.2

After fainting several times, I finally wake up. I am lying on a bed. Although my body is extremely weak, as if a tide has receded from the top of my head, my mind is gradually becoming clear: so everything is finally happening. So quick! I don’t know what time it is. Do my friends know I am missing? Tomorrow at the latest, Huanhuan will go to the office and should realize that I never returned after I left. Surely she will inform Teng Biao.

After looking around, I guess that I am in a hostel in the suburbs. The room is about 12 square meters; the door and toilet are to the north, and a window to the south. A writing desk and a chair, originally on the side facing east, have been stacked together and moved to under the window. In their place, there is a stool against the wall, where I hit my head previously. To the west is the bed I am lying on now. There are five or six people walking back and forth, whispering to each other. Someone realizes that I am awake.

Before the interrogation, I set two rules for myself: First, death by starvation is trivial compared to the loss of integrity. I can talk about myself, but will never name my friends. Second, it is better to be jade smashed to pieces than a tile kept intact. Now that I am here, I have to prepare for the worst.

The Face-off

I struggle to sit up from the bed and lean against the headboard. A wave of stabbing pain comes over my back; I don’t know when I got injured.

The interrogation begins. As other people leave the room, only No. 1 remains (I am numbering interrogators in order of appearance). He looks to be around 30 years old. His hair sweeps up with the help of a thick coat of mousse. A narrow-waisted, short-sleeved shirt hangs on his body, with the collar open to reveal a silver necklace that weighs at least a kilogram. I really want to tell him: it looks like a chain for a dog — ugly.

He twists his wrists with exaggeration, lights up a cigarette, and places it in a cigarette holder that is transparent. He uses two fingers (one with a silver ring) to hold it, as his fingers spread out like an orchid. He strolls toward me and plops down close to me on the bed. I lower my head to ignore him. A few moments later, he uses one finger to press on my forehead to lift up my head, and tuck a lock of my hair behind my ear. He then takes a deep drag of his cigarette and blows smoke slowly at my face. Obviously he wants to provoke me. I close my eyes; I am not fooled. Sometime later (it feels like a century), he puts his arms gently on my legs, his body leaning forward, almost whispering to me: “Look at me.Look at me!”

I look up, unmoved, but make eye contact with him as he stares flirtingly. He raises one eyebrow and moves closer to me, less than one foot away, while making goo-goo eyes.

“Please keep away from me!” I try hard to sound strong.

“How far?”

“As far as possible.”

“Why?”

“I hate smoke.”

He gets up, walks to the table, puts out the cigarette, and comes back.

“Look, no more cigarette. Now isn’t it time to talk? What is your name?”

“I have nothing to tell you. Bring your boss here.”

I close my eyes and ignore him.

This little punk has plenty of patience and begins a monologue that lasts for almost an hour. A man comes in, whispers in his ear, and quickly leaves. A moment later, another group of four to five people comes in. One of them looks familiar. He looks like Captain Zhou of Domestic Security3 in the Dongcheng [Eastern] District of Beijing. Several months ago he summoned me for a “chat.” On that occasion, we sat across a table. Although his words were threatening, he kept a smile the entire time. Now the person before me looks stone-faced, wears sun-glasses, and is shorter than the one I remember. It’s clear that he only has a supporting role in this kidnapping. Therefore, at this moment, I’m afraid I can’t be sure.

“Get up and follow us!” someone orders.

I move to one side of the bed and put on my shoes. As soon as I touch ground, the pain is so excruciating that I’m immediately drenched in cold sweat. My ankle is injured. Before I can think, the black hood comes down again. Dragged and lifted by two men, I stumble out of my cell. We walk down a long corridor and pass through a gate. I am stuffed into a vehicle like merchandise.

The vehicle soon comes to a stop. I am led into a big room, and after ten steps or so, I arrive at another room. I am pressed down onto a square stool. Immediately, the din from the people inside the room subsides. Only one person is left walking slowly around me. In the quiet room, his footsteps are the only sound, one circle after another. He stops and snatches off my black hood. Probably because I have gotten used to the darkness, the light is so harsh that I cannot open my eyes.

“What is your name?”

I see them clearly: a pair of hiking boots. I look up slowly: hiking pants, a blue athletic shirt, a leisure jacket. He is a pale-skinned young man, with eyes as big as those of an antelope — No. 2. He looks like the outdoorsy type.

“What is your name?” he asks again.

“You don’t know who I am, and you kidnapped me?”

“Just answer my question.”

“Hua Ze.”

My eyes have adjusted to the environment. Looking around, I am sitting in the middle of a room that is about 20-30 square meters. There are two chairs and a desk roughly three meters in front of me, with a square briefcase on top. It is a recorder. A classic scene of interrogation you often see in movies.

“Did you just get off the airplane this afternoon?”

“Correct.”

“From where?”

“Dandong.”

“What were you doing?”

“Shooting a movie.”

“How many days were you there?”

“Three days.”

“What did you film?”

“A lawyer working on a case.”

“What did they do?”

“Interview relevant parties and their families and photocopy files in the court and procuratorate.”

“You need three days for all this?”

“We still did not have enough time.”

“Who is the lawyer?”

“I do not want to say.”

“Why not?”

“I do not want to mention names.”

He walks back and forth again, saying: “You look very weak.”

“I am in pain and tired and I can’t sit.”

He brings a chair to me: “Sit down then. Better?”

“Yes. Thanks.”

“Shall we continue?”

“Go ahead.”

“Why did you film this particular lawyer?”

“I like to.”

“Why do you like to?”

“Do you have to have a reason?”

“Why not?”

“I do not need a reason to like.”

I hear him take several deep breaths. He pauses for a moment, and then resumes.

“Where will you broadcast it afterwards?”

“Whoever pays for it will broadcast it. If CCTV4 wants it, I have no problem [selling it to them].”

“If no one wants it, then what?”

“Then I will dedicate it to people I like.”

“Are you just going to film this one lawyer, or do you plan on having a series?”

“I am not sure. If I find someone I like, then I will do it again.”

“What do you mean by ‘like’?”

“You won’t understand, even if I explain.”

“How did you know this lawyer?”

“Too far back to remember.”

He keeps trying to find out more about the lawyer and the filming but gets nothing.

“Pang!” The door is pushed open. A tall man makes his grand entrance escorted by four or five men.

No. 3 is about forty years old, small-eyed, and in Western clothes. His shoes are so polished that even a fly would slip off of them. He plops his cigarette pack and mobile phone on the desk, and sits down. He crosses his legs. He shakes his legs nonstop and says furiously: “Don’t mess with my brothers. Didn’t you say you wanted to see the leader? Here I am. I must tell you, I am too busy to talk nonsense with you. You’d better be forthcoming. Will you chat?”

“Haven’t I been chatting with your brothers?”

“This can’t continue — it’s going nowhere. One moment you say you can’t remember; another moment you say you don’t want to talk. You call this chatting? In here, you still want to call the shots? No way! Let me tell you: Anyone who comes in here can’t get out easily. Whatever I ask, you answer. That’s what we call a chat, understand?”

“Would you please show me your ID? Which department are you with?”

“If I tell you, you will be scared to death.”

I am wondering: I have dealt with Domestic Security for one or two days and have never felt scared. Maybe they are the State Security?5 “Tell me then.”

“I can’t tell you now. Later.”

I laugh. No. 3 becomes so upset that he is gnashing his teeth, and his face is contorted.

“Do you believe that I can make you disappear from this world right now?”

I continue to laugh and stare at him as if watching a show. Then I hear a dog barking outside.

“Believe me — I will bring the wolf dog in to play with you.”

“Okay!” I’m laughing so hard that I can’t collect myself.

No. 2, who is standing next to him, jumps in to help:

“Why are you so arrogant? What’s so funny? You should be scared, like normal people who are brought here.”

“Why should I feel scared? You guys kidnapped a totally defenseless woman and don’t even dare reveal your identities or names. This tells me that you are even more scared than I am. Since you are so scared, there’s no need for me to be.”

No. 3 is clearly furious. He bangs the desk: “I am asking you for the last time, will we chat or not?”

“There’s nothing to chat about.”

“Fine, you want to be Sister Jiang?6 I will lend you a hand. I always show courtesy before using force. Now that the courtesies are over, it’s time for the rough stuff. You just wait!” After he finishes, he charges out the door as if he’s fleeing. All the men in the room swarm out after him.

I throw this sentence at him right before he leaves:

“Since being kidnapped, I have never expected to leave alive.”

The door slams shut and then opens again. Here comes No. 4. He shouts at me: “Stand up! Getting comfortable sitting?”

As soon as I stagger up, he kicks away the chair under me.

“Do you have a proper line of work?”

I look at him, puzzled: what does he mean?

“You have no man, and no proper line of work.”

Now I understand. “You think what you are doing is a proper line of work?”

“You just shut up! Our leader is showing you respect by asking you questions. You call that an answer? That’s worse than not answering. If you answer like that, it would be better that you not talk at all.”

It’s true that I don’t have much to say to this scrawny, cowardly man.

“Why don’t you find a man? Why don’t you find a proper line of work? What are you now?”

What kind of logic is this?! Has this guy ever gone to school?

He repeats numerous times these two ridiculous sentences. It seems that he is very concerned about my not having a man or a proper line of work.

I look at him, speechless.

“Well, you don’t speak. Why don’t you speak?”

I am wondering: Isn’t he the one who just told me it is better not to speak?

In anger he circles around and stops behind me. “Courtesy” is over. Will the rough stuff begin? What kind of rough stuff? All the cruel punishments I have heard of are flashing through my mind. I remember what someone I know often says: the most despicable people are the ones who cower when they’re taken in and act tough when they come out. I’m not going to give this person an opportunity to judge me that way. What’s more, my body would probably give out after a few shakes, so the pain would not last long. I am ready for it.

Why doesn’t he start? How long has it been? My right foot hurts so much that I shifted all my weight to the left foot. I’m now in a daze. Don’t collapse, please, never! Don’t let them think that I’m scared.

I start to hear someone talking to me. I’m slowly regaining my consciousness. It is No. 2. He brings back the chair for me to sit down. He starts to play the good guy: “Why are you shivering?”

“Cold!”

He leaves for a while and comes back with a white bed sheet: “I didn’t find any clothing. Take this instead.”

I wrap myself in the sheet. No. 2 pulls up another chair and sits next to me. He starts talking in a heartfelt way. “Why are you so stubborn? Actually we just want you to have a good attitude.”

“In broad daylight, you guys illegally kidnapped a law-abiding citizen and brought me here. What qualifies you to talk about ‘good attitude’ with me?”

“If you keep trying to find out how you got here, this thing will never end. You cannot change reality.”

“I know I cannot change reality, but I can refuse to cooperate. It is not possible for me to cooperate with even little thugs.”

“Little thugs? Who are the little thugs?”

“Those who harass me, those who want to make me disappear from this world. I can bear big thugs, but not little ones.”

“What is the difference?”

“Big thugs try hard to conceal their nature, for they know it is ugly. Little thugs nakedly play out their thug nature, because they think the ugly is beautiful.”

“Oh, that sounds right. But you are too arrogant, don’t you know? Do you realize that? Your attitude makes people feel provoked.”

I correct him: “I’m not trying to provoke you — that would be beneath me. To make me disappear? Don’t play this game with me.”The more I talk the angrier I get. “It’s just death, isn’t it? We taxpayers spend money to support you evildoers. Seeing and hearing about your evil deeds every day has made me tired of living for a long time.”

With patience, he says: “Have you thought about this? We may not let you die, but just let you waste away. Could you stand that?”

“So just let me waste away. Once the oil dries up, the light will go out.”

“Why can’t you go along with this? Isn’t what you do respectable? Why can’t you talk about it?”

“I have already told you, I can talk about myself, but not others.”

“Even now, you are still thinking of others? You don’t even know whether you can get out of here.”

“For me, the peace of my inner heart and the freedom of my soul are more important than the freedom of my body. You couldn’t understand.”

He pauses in silence for a while: “Let me think about this. You also think about it some more. It’s too late for tonight. You can rest.”

I ask to use the toilet. He calls a female guard to accompany me. When I come out, I see a mattress with bedding on the floor. The female guard says: “Just make do with this for sleep.”

What? That’s all? No torture? No wasting me away? Regardless, let me just lie down and warm my weak and shivering body.

A man and a woman move two chairs to sit beside my mattress. For the first time in my life, I close my eyes under the light of a 200-watt bulb and the watch of two guards.

Although exhausted, I have a sleepless night and can feel my heart pounding hard in my chest. My whole body starts aching: shoulders, abdomen, and four limbs. Probably the result of the hysterical struggle I put up when I was being kidnapped. I exerted too much force.

I lie there resigned. As they change guards, the footsteps, the murmurs, the squeaks of chairs, and the sound of breathing are all so vivid. I don’t know what time it is. Daylight is piercing through the thick window curtain. The room faces south. A short and stout man enters. (I know this hired thug is one of the kidnappers from yesterday!) As he walks towards me, he keeps his hands in his pants’ pockets. He stares at me with a vicious look. He kicks the mattress twice: “Get up! You think you’re here to recuperate?”

I get up, make my bed, and then sit on the mattress silently.

No. 2 comes in, pulls up a chair, and sits next to me.

We continue our topic from yesterday.

“Let me repeat: I will only talk about me, nobody else.”

“Is this your principle?”

“Yes.”

…

“What does your name Hua Ze mean?”

“It means the ocean of flowers. Classical Chinese does not distinguish between the Hua that means flower and the Hua that means grand.”

He starts to ask me about some trivial things, which seem boring to me, but perhaps are important to him: my family background, my upbringing, my education, etc. The conversation flows aimlessly.

“From yesterday to today, there have been 20 to 30 people who have handled me. Is this how you waste taxpayers’ money?” I ask.

“How do you know we are spending taxpayers’ money?” He looks at me full of interest.

“You’re not?”

“Not necessarily.”

“Don’t tell me that you get paid by Anyuanding.”7

“It’s hard to say.”

“Working this job must be very painful, right? It haunts you, doesn’t it?”

“How can you be so sure?”

“You look educated – at least a college graduate. Will you tell your family that you kidnapped me?”

“You can’t say that this is a kidnapping.”

“Then what is it?”

“We call it: ‘taking in.’”

“Do you realize this is illegal?”

“Laws consist of many layers, some you know about, and others you don’t.”

“Oh, that’s new to me. What I don’t know is also called law.” I look at him with curiosity: “Tell me, which department are you from?”

“Even if I tell you, you will not understand. Even if in the future we see each other on another occasion, you will still not understand.”

“Then just tell me your name. Even though you are a member of this organized criminal gang, someday when you are on trial, I can testify in court that you did not torture me while I was kidnapped.”

He chuckles, “When do you think this day will come?”

“Heaven’s plans outstrip man’s. It may take ten years, or just one night. But I believe in our life time, you and I will both see this day.”

“Then what do you plan to do before this day?”

“To use my pen, my heart, and my camcorder to make a record of the changes of these times.”

He nods and changes the topic, “You should eat something. What would you like?”

“I would like to brush my teeth first. If I don’t brush my teeth, I can’t eat anything.”

He spends the next ten-plus minutes trying to convince me that rinsing with water can also clean my mouth. I insist that I must use a toothbrush and toothpaste.

Finally he says, “In fact, it wouldn’t be too hard to find a toothbrush, but you seemed emotionally unstable last night. I am concerned you would hurt yourself.”

“So that’s how it is! While I sleep I have someone by my side. When I go to the toilet, I also have a ‘bodyguard’ next to me – all because you are afraid I will commit suicide?”

“Yes, you did not even blink an eye yesterday when you talked about death. That scared me.”

Now it is my turn to laugh: “Take it easy, I won’t kill myself. But if I did, my blood would be on your hands.”

“If you are killed here, no one would know.”

“I wouldn’t be so sure of that. Is there not one among the twenty or thirty of you who has a conscience? Even if no one speaks out today, how can you guarantee that no one will speak out ten or twenty years from now? Don’t be so self-confident.”

“Are you really not afraid of death?’

“However you live, you only live once. It’s better to live a short and meaningful life than a long and ordinary one. So what is there to be afraid of?”

“Then you must eat something, and take good care of your body, so you will be able to live brilliantly.”

“I must finish brushing my teeth before eating anything.”

“You’re so stubborn, you know? Many of your friends are smarter than you are.”

“I know.”

The result of this negotiation is that I have to use my fingers to brush my teeth with toothpaste. Then I eat a few pieces of green vegetables, mushrooms, and some instant noodles.

No. 2 leaves. Two guards immediately come in and sit on either side of me. It seems I can continue to rest.

That ends today’s “talk”. What do they want? They made such an effort to kidnap me to just let me stay? Clearly, we cannot understand each other. We are not the same kind of people. The difference between us is much greater than that between a wolf and dog.

It’s so quiet, except for the barking of dogs. Occasionally, you hear the rumble of a passing airplane. I guess I am east of the airport. Is this a secret place specifically used to lock up dissidents like me? How many secret places like this do they have? How many dissidents have they locked up? Did they torture people here? Can those who get out of here return to a normal life? Just one year ago I could never have imagined my current situation. My thoughts are running wild. It turns dark and then bright.

The hired thug returns and kicks my mattress. I turn over and show him my back. He lifts off my covers. I keep still and ignore him. He gets mad and walks around my mattress twice. Then he starts yelling and cursing: “You cheap bitch. Who do you think you are? What the fuck are you pretending to be?” He goes on and on with disgusting words that I cannot put on paper.

I gather my courage and sit up suddenly: “What are you? Get out of here!”

He comes closer to me: “Say it again? I’ll kill you!”

No. 2 rushes in. I shout to him: “Keep this hatchet man off me. When you want to kill me, then you let him in.”

No. 2 stops the hatchet man who is rushing at me. Before he leaves, he points his finger at me: “You just wait! I’ll drag you out, dig a pit, and bury you!”

I’m shaking with rage: “I wait to be buried by you guys. I know you’d do it. But keep in mind, there’ll be a day when you are tried!”

This is the third day after being kidnapped. How can I let my friends outside know where I am?

There are at least five shifts of people guarding me. There are one man and one woman in every shift, which changes approximately every two hours. Every time No. 2 comes in, the guards leave immediately; when he leaves, they come back right away. Judging from their brief conversations, they come from different departments. They may know nothing about my background. If I talk loudly to myself, letting them know who I am, how I was kidnapped, will one of them send out a message for me? I don’t believe that all the people I have come into contact with are cold-hearted. I bury my head in my knees and think quietly.

“Pang!” The door is pushed open. A gang of men rush in. One of them sits close to me on the mattress. This is No. 1, the little hooligan. He pokes at my ribs with his elbow: “Raise your head! Look at me!”

I don’t move and keep silent. He pokes again, and again. I still keep silent. He lights his cigarette, takes a drag, finds a perfect spot, and blows the smoke at me through the space between my head and elbows. I move away from him and keep burying my head. He continues to move close to me: “Hello, why are you so calm? Trained in Taiwan?” Laughter breaks out from others.

Judging from this, again I’m sure that they are not from Domestic Security, but State Security. Perhaps they have been told that I am a spy and special agent, have endangered state security, and therefore, have become an enemy of the state. Otherwise, how can these educated young people do such wicked things without feeling a bit of unease in their conscience? How can you make them believe what they do has any dignity? At this moment, they clearly have come not to interrogate me, but to have some fun while they are bored. I keep silent with my head buried. After they have messed around for a while, they lose interest. The entire gang walks out in a drove.

Afterwards, No. 2 comes in occasionally to stand around and chat with me. I realize that he is trying to figure out what is in my backpack. “Is your backpack for a video recorder or camera?”

“For both.”

“Where are they?”

“I left them at a friend’s home.”

He tries to figure out what the SD cards are for. Since these cards are for professional use, he cannot see the data inside by using an ordinary camera.

“Did you make the April 16th documentary?”8

“Yes.”

“It wasn’t that good. Any storyteller can do it. It had no technique.”

“Thank you for your compliment. The highest achievement in making a documentary is the invisibility of technique.”

“Why do you care about these people?”

“I love them.”

“Are you kidding? You love so many people, but are not married.”

“The love I am talking about is different from yours.”

He has been watching the April 16th documentary. Is he moved by the scenes that have affected so many? I want to tell him: that is love.

“How many mobile phones do you have?”

“Several.”

“Why did you take them apart?”

“To clean them.”

“Why keep them off?”

“To save battery life.”

He is examining my mobile phones. I have two. The one I use exclusively for Twitter was bought a few months ago. He’s touched it. It’s dirty now.

“Your life was not bad; you have been to quite a few countries.”

“Yes. My dream is to travel around the world.”

Is he looking at the pictures I took? There is nothing in my USB drive. Is he reading my blog?

“You made a lot of money?”

“Every penny I make is clean.”

“Don’t you wish to return to your past life?”

“I wish it every day. But I can’t go back.”

“We can help you.”

“You? Help me? How? Will you make the kidney stone babies healthy again?9 Will you release Zhao Lianhai?10Will you bring back to life all the school children killed by the collapse of the shoddily constructed school buildings in the Wenchuan earthquake?”11

“Is there a single thing in this country that you are satisfied with?”

“I just want to ask you one question: Why did you kidnap me? Did I break the law? Would any government in a civilized country do things like this?”

“Of course, the American CIA kidnaps people too.”

“Young man, you’ve probably watched too many American blockbuster movies. The CIA only operates abroad, not domestically. There’s no way it kidnaps citizens at home.”

“Do you ever know how to compromise?”

“People with different interests can compromise, but how do you compromise with thugs? How do you compromise with the man who rapes you? If he says he will rape you ten times, do you compromise at two times? He says he will do it for one hour, would you compromise at twenty minutes? ”

Then he turns and walks out.

After another sleepless night, I get up feeling extremely weak. My denim overalls have become loose. I put on my shoes and stand up unsteadily, stepping on the bottom of the jeans’ legs. I bend down to roll it up. As I try to stand up again, I blackout.

I hear a hubbub; it seems very far away. Someone is pinching me just beneath the nose, the fingernails almost piercing to my bone. I open my eyes in pain and see the gloating face of the hatchet man. I am lying there, face-up and helpless. Five or six men surround me, including No. 3 and Captain Zhou from the Beijing Dongcheng District Domestic Security detachment. Now I’m sure that is him, although he still wears sunglasses and doesn’t say a word.

“Get up, put on your jacket, and follow us.”

I am carried away. The black hood is put on me for the third time, and I am pushed into the backseat of a car. With two men sandwiching me on both sides, I leave the place where I have been imprisoned for four days.

Unsure of where I am being taken, I try to guess the directions. The car zigzags continuously. A call comes in. I can tell Captain Zhou is sitting in the front passenger seat answering the phone. I hear a long sigh from him. It sounds like this assignment has not been handled very well. After roughly two hours, I hear the announcement through the train station’s loudspeaker: “Attention please! Passengers… ” I realize they are sending me back to my hometown.

“Where are you sending me? I have no clean clothes with me. You have to notify my family.” I tore off the black hood. The two men yell at me loudly and force the hood back on me. The man sitting on my right pinned my head down with his hands. My chin is pushed against my chest and I cannot move at all. The part of my back that was injured on the day of the kidnapping hurts so much that it feels as if it were splitting open. As I resist, I scream loudly: “Let go of me!” Captain Zhou in the front seat orders me to stay quiet. The man on my right grips my hands tightly and squeezes them. “You want to fight? Then fight!” His voice is so low, only I can hear. It is the hatchet man again. He is getting his revenge!

Captain Zhou opens the door and gets out. As the hatchet man tries to twist my wrist to my back, he curses through his teeth: “You want to shout? Go on! Aren’t you so tough? I’m going to crush you! Crush you, you cheap bitch!”

I struck back loudly: “You, the dregs of mankind, are not even fit to carry my shoes! You can kill me if you dare!”

My wrist is twisted by him to form a 30 degree sharp angle. I have spasms in all four limbs and gradually they become numb and lose feeling.

Captain Zhou returns to the car. The car starts and then stops after a short distance.

“Get out!”

“I cannot move my leg.”

“Damn, what are you faking?”

The hired thug kicks me and drags me out. Before I am dragged out of the car, the black hood is removed.

I am standing on the train platform, just in front of a car. The bright sunshine of late autumn shines on my face.

In broad daylight, in clear view of the whole world, I was kidnapped openly and dragged on the ground by two men. I cannot hold my tears any more. They pour down.

I cry out: “Let go of me! Let go of me!”

Someone grabs me from behind: “You cannot treat her this way. You let go of her.”

I look up and ask: “Who are you?”

“I am Chen Ming.” (A pseudonym.)

“Ah, Chen Ming? Is it you?”

“Yes, it’s me, Chen Ming, to accompany you back to Xinyu.”

Chen Ming is the office director of Xinyu Broadcasting and Television Bureau and the husband of my friend. After many years of not seeing each other, we are meeting here in this manner.

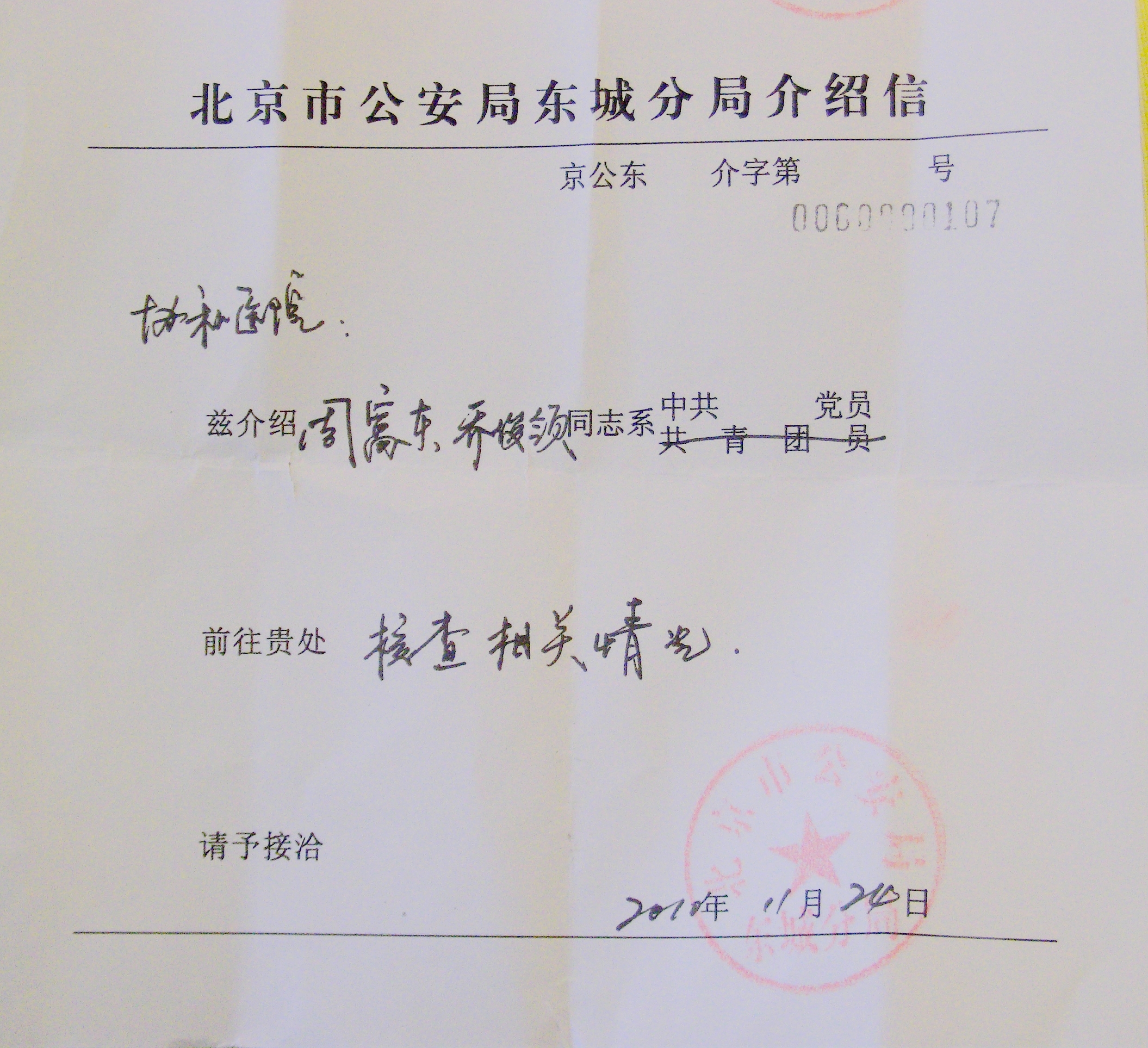

Chen Ming carries me to the train, my limbs all numb. The passengers have not been allowed on board, so there is only Chen Ming, myself, and two Domestic Security officers who claim to be plain clothes policemen working for the neighborhood sub-district office.

Forty minutes later, the train leaves the Beijing West Station. After a total of 68 hours, I’m finally leaving the evil grip of a criminal gang and starting my soft detention.

House Arrest

Xinyu is a provincial city in Jiangxi Province. Twenty-one years ago, I was a reporter for The Xinyu Daily. After resigning in 1989, I went through a period of roaming. I do not remember exactly which year I returned to Xinyu to process my passport application. At the time, since my household registration was still with the collective registration system at the newspaper, I had to travel a thousand miles just to get a confirmation certificate. I asked my good friend Jianjian, Chen Ming’s wife, to let me register my household under hers so that she could help me handle this kind of bureaucratic minutiae. And just like that, Chen Ming became my “head of household.”

Approximately one month before I was kidnapped, Domestic Security agents contacted Chen Ming to get background information on me and informed him that I was involved in some major rights defense activities. Chen Ming went home and asked Jianjian: “Could it really be Hua Ze? Would she be involved in these kinds of activities?” Jianjian was sure: “It’s her, alright. I know her.”

On the evening of October 28, Chen Ming was notified by his superior that he should go with the municipal Domestic Security personnel to pick me up in Beijing, and that his work unit would pay for all of the expenses of this trip. I don’t know whether Chen Ming regretted having allowed me to transfer my household registration to his household. I don’t know if he was reprimanded by his superior for choosing friends carelessly. In short, Chen Ming and his work unit were implicated by me.

As soon as I boarded the train to Jiangxi, I asked to check my backpack. A plainclothes officer hands me my backpack, and as I unzip it, my mobile phone falls out. A female officer in plainclothes snatches it away: “I’ll keep it for you.” What she does not realize is I have another phone which I use exclusively for Twitter, and never for phone calls. It is as clean as a newborn baby. When I was on an assignment in the northeast, I had only one battery for the phone with which I make calls. As a precaution, I saved two friends’ phone numbers on my Twitter phone. If I rely on my memory and don’t save numbers on the phone, I cannot even remember my own home phone number. This precaution will save me from many troubles.

I quietly put the remaining phone into my pants pocket. After the train starts, I go to the bathroom to make two phone calls. First I dial Pu Zhiqiang’s number. It rings for a long time, and he does not answer. Then I dial Teng Biao. As we talk, there is a lot of background noise and we have an off-and-on connection. I tell him that I have been kidnapped and that among my kidnappers was a Domestic Security officer from Dongcheng District. I am now being taken to Xinyu, Jiangxi, and my laptop is still at the airport. I ask him to find a way to get it to me. I can barely finish a few sentences before the phone is disconnected. Then Zhiqiang calls and tells me he has been under house arrest since he returned to Beijing from Yichun on October 27, but he can still make contact with the outside world. I repeat for him what I said to Teng Biao. He pauses and then tells me with a cautious tone: “This is the life you have chosen. This was bound to happen sooner or later. You must learn how to face it alone.” I answer: “Yes, I know.”

Later, over the fifty days of being cut off from the outside world, I thought of these words many times. I regard them as advice from a forerunner to a follower, because this is our life.

After making these two calls, my cell phone battery has only one bar left. I don’t know what awaits me, and must keep this last bar to call for help when danger comes. Even though I don’t know who would be able to help me or how they would help me, I cannot let myself disappear in this way – I must let my friends know about my situation.

On the train, the two plainclothes officers who came to get me ask with curiosity about Liu Xiaobo. This is the first time since I have lost my freedom that someone has mentioned this name to me.

“What is your relationship with Liu Xiaobo?

“What has Liu Xiaobo done? …”

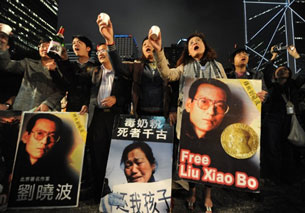

My hunch is confirmed: all this is because I signed the “Statement Regarding Liu Xiaobo Being Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.” I gave my name, Hua Ze; place of residence, Beijing; and occupation, documentary director. So it was just for these few words that they kidnapped me and will continue to imprison me. It also becomes clear that my kidnappers are from State Security.

This is a barbaric state and a criminal government. Rules of civilized societies are not followed here. Compared to the end of the Qing Dynasty one hundred years ago, the only difference is dissidents of that time had their heads chopped off and were forced into exile, but now they are kidnapped and made to disappear. All this must change!

Then I start to talk about June 4, 1989, Charter 08, the Nobel Peace Prize, etc. Talking about these topics starts to fill me with excitement. Since the authorities want to use kidnapping and imprisonment to allow me to share Xiaobo’s honor, I must live up to his name. I must continue to sow the seeds of fire.

As the train approaches our destination, the two plainclothes officers and Chen Ming all say to me, “We are only responsible for picking you up. We will not see you again after we get to Xinyu. We hope you will know when to back down so as not to get hurt – bend when you have to.”

I thank them with a smile for their kindness. But the word “bend” is not in my dictionary.

At the Xinyu train station, Mr. Chen Jianjun, a Domestic Security officer from the city, comes to pick me up. He is about 40 years old, and you could tell in a glance that he has a soldier’s background and is not well-educated. As soon as we get into the car, he starts lecturing, saying things like:

“Don’t wash the family’s dirty linen in public. When you bring domestic problems to the international community, you are damaging the country’s image.”

“You shouldn’t exploit the loopholes in the law and use the law as a weapon; the law is not everything.”

“Maybe your intentions are good, but you have been manipulated by foreign, anti-Chinese forces.”

Even though I am not good with clichés, when I see that he is so thoroughly brainwashed, I have to respond patiently:

“It is precisely out of a concern for our country’s image that we appeal for the release of Liu Xiaobo. How can you keep a Nobel laureate in jail? To win a Nobel Prize had been one of China’s dreams for a century!”

“Laws are made by the ruling party. How can you say that to maintain the integrity of the law is to exploit its loopholes? If we don’t use the law as a weapon, then should we use tanks?”

“As for the anti-Chinese forces, I still want to know how they have manipulated me.”

He says: “I don’t understand you. We’ll talk later.”

Then I tell him with a solemn tone: “If you don’t know me, then don’t tag me with an unfair label. Come back to talk with me after you have spent some time trying to understand me.”

I despise those who lack professionalism. Why is it that everyone I have met throughout this ordeal is so unprofessional? Why can’t they at least devote some thought to understanding me? Don’t they realize that I am more easily convinced by softness than by harshness? I believe that even for such shameless professions as Domestic Security and State Security, some degree of professionalism should be maintained.

After arriving in Xinyu, I am sent directly to the Xiaofang Guesthouse, a six-story building located on the northern edge of the city. Initially, it must have been built in accordance with the three-star standard, but now it looks somewhat dated. Fortunately, the bedding is still reasonably soft and clean, and the bathroom is also quite spacious. I am housed in Room 9207 on the second floor, which is reportedly the only room in this guesthouse that accommodates three people. There are two female police officers rooming with me, and two other male officers next door. There are four guards in every shift, and two shifts in total, rotating every 24 hours. All together, I have eight personal “bodyguards.”

As soon as I step into the room, Ms. Ouyang of Domestic Security announces several rules: I may not have contact with the outside world, I may not meet with friends, and the scope of my activities may not go beyond this building.

When the bodyguards introduce themselves, they give only their last names, not their first names. They say they are criminal police, economic police, or public security police. None of them admit to being a Domestic Security officer. Apparently, this kind of police – domestic security – is just too shady. However, having seen so many Domestic Security officers, I can recognize them at a glance. Of the eight, three are from the Domestic Security detachment of the municipal public security bureau, and the rest have all been transferred from different public security sub-bureaus. My security level is higher than anything they have ever experienced. Even their superiors know only that they have been transferred to carry out an assignment. As for where and what the assignment is, that is all classified.

Captain Hu of the municipal Domestic Security detachment has come – he says he is the leader, but no one mentions his position. After a while I figure it out by myself. The leader is very polite and says: “This is a coordinated action by the Ministry of Public Security, so how long you will stay here depends on the orders from above. The Xinyu authorities do not want to keep you a minute longer, and hopefully you will cooperate.” He advises me to regard this as a vacation or recuperation.

I ask Captain Hu to allow me call my mother to tell her I am okay. My mother is almost seventy. She must be worried after not having heard from me for so long. Captain Hu says that he has to consult his superiors for instructions.

No one comes to talk with me, and no one comes to explain to me the reasons for the restrictions on my freedom. In short, my life under house arrest has started, but with no end in sight.

I go to the bathroom and send a text message to Teng Biao: “I am living in Room 9207 at the Xiaofang Guesthouse in Xinyu. The police here have been polite to me, so please don’t worry too much.” My mobile phone has little power left, so I cannot wait for a response. I turn it off immediately.

Then I take a shower. I have been wearing the same clothes for five days, whether I’m sleeping on the bed or lying on the ground. I cannot bear it for one more minute.

I take off my clothes and inspect the painful “rewards” from the past four days since being kidnapped. The crescent-shaped cut on my upper lip is so deep that even a slight touch causes piercing pain. The wound on my back is below my neck, which makes it impossible for me to turn over as I sleep. All four of my limbs, especially my right arm, are covered with black and blue bruises. My right foot is sprained. The wounds on my upper lip and right hand were inflicted by the hatchet man on the day of the kidnapping. But how did I get the other injuries? I fainted several times on that day, so I can scarcely remember what they did to me.

After showering I am completely exhausted. I lie on the bed near the window, peeking at the sky of Xinyu through the iron bars on the window. I have no relatives here, so it is a completely strange city for me. I don’t even have any idea where this guesthouse is located.

I have to get used to sleeping with two bodyguards in the same room. I hope that they will not snore, grind their teeth, or talk in their sleep. After a long time with insomnia, I have become very particular about my sleeping environment. It has to be very quiet and clean.

The trip to Europe I had planned for November has become impossible. Exit restrictions will probably be imposed on me; my dream to travel around the world might have just ended. Has Teng Biao retrieved my laptop? I hope it’s not in the hands of the thugs. For the first time, I am going to have bad credit at my bank: I have missed the payment due date on my credit card. I spent more than 20,000 yuan for the plane ticket to Europe – there must be a lot of interest. What should I do about my daily medicine that I didn’t bring? What are the health consequences?

Why am I worrying about all these mundane issues? Without freedom, what else is worth worrying about? So what if I cannot travel all over the world, since there are so many people who have never even stepped outside of the city of Beijing. So what if my credit is not good, I have no plans to apply for loans anyway. Teng Biao will find a way to get back my laptop, and even if he cannot get it back, I will accept that. What does it matter if I cannot take my medicine – I was already prepared to die when I was kidnapped. My only worry is my mother who has a serious heart ailment. On the evening of October 8, when the Nobel Committee announced the Peace Prize, many of my friends were arrested as they were gathering in restaurants to celebrate. The next day my mother left Beijing for Jiangxi. As I said goodbye to her at the train station, I promised: “I’ll be fine. Don’t worry.” Now I only want to say to her: “I’m sorry, Mama. I did not keep my promise.”

Now that I am stuck here, I have to take it easy. It’s no use being anxious and angry – that will only impair my sharpness and judgment. I try to comfort myself: “It’s fine. Just take this as an opportunity to train your ability to stay calm.”

The next morning, Chen Jianjun from Domestic Security, who had picked up me at the train station, opens the door and comes in. As he takes a phone call, he points at me: “Did you contact someone in Beijing? Do you still have a communication device?” He turns back and gestures to the two female bodyguards: “Search her body, her backpack, and the bed!” My mobile phone is confiscated, and with it the last hope for me to be able to contact the outside world. With it they also take away some of my professional equipment: a wireless walkie-talkie and a camcorder. They do not know what they are used for, but they take everything away just to be sure.

The only thing left in my backpack is the instruction manual for my camcorder. Since I’m still new at videotaping by myself, I cannot remember all of the functions of the camcorder. I have the manual with me so that I can consult it when I need to. In the coming days, this manual will be my only reading material.

Every day I go through the same routine:

At 7:30 a.m., I get up, wash and brush my teeth, and then I go downstairs to have breakfast. In the morning: I read, write in my diary, and practice yoga. At 11:30 a.m., I have lunch. In the afternoon, I read, practice Pilates (a hybrid of yoga and aerobics), and take a shower. After dinner, I watch some TV and then go to bed.

At the very beginning I couldn’t get used to the environment. The bodyguards would keep the TV set on from morning to night. The noise was unsettling but luckily I soon learned how to read, write, and do exercise with the TV sound on.

One day after dinner I ask to take a walk outside. Chen Jianjun calls his superior for permission. He replies: “Walking is allowed, but not beyond the courtyard of the guesthouse.” So there is one more activity in my life.

Every evening, I wear my red wool sweater, suspender jeans, and a black coat (they are all the clothes I had with me when I was kidnapped) and circle the courtyard twenty times surrounded by four bodyguards. The scene must be very funny.

There are only a few guests in the guesthouse. The courtyard is a rectangle, 80 steps from east to west, and 35 from north to south. There are only two rooms with windows secured with steel bars. My Room, 9207, is one of them. During the first walk, I discover a moderately-sized Osmanthus tree in the southeast corner. This green plant with small white and yellow flowers and a strong fragrance has brought some life to my daily routine.

On the first day of my arrival to Xinyu, I made a request to call my mother. After a week, I have heard no response. On November 9, at breakfast, I make my request again. Chen Jianjun replies: “It would not have been out of the question for us to let you call your mother, but you hid your phone and contacted the outside. This incident has serious consequences. So we cannot let you call your mother.”

“What serious consequences have I caused?”

“I cannot tell you.”

I immediately burst out: “Even if I were a criminal, you would still have to notify my family. But you are treating a law-abiding citizen without the slightest bit of humanity. I had an extra mobile phone and the Beijing police did not inform you about it when I was transferred to you. This is not my problem. Anyway, it is my right to inform my friends about my whereabouts. Are you punishing me for that? Go ahead. Are you afraid that I will contact the outside? Starting now, I will begin a hunger strike! When I collapse, you will have to take me to a hospital – won’t you? When I get to the hospital, I will scream for help and tell everyone that you have kidnapped me.” After I finish these words, I leave the dinner table and walk out. I can hear the footsteps of a few people chasing after me.

“Little Chen does not know much. Please don’t take him too seriously.”

“There is nothing wrong with not knowing much. But you cannot lose your humanity. Everyone has parents.”

“We cannot decide whether you can call your mother or not. We have to send a request to our superiors.”

“I have already given you nine days. Even if you had to go through the UN, it should have been done by now.”

I return to the room and launch my first hunger strike – for the right to call my mother!

In the morning, Captain Hu comes: “I am sending my request to the leader right away. It should not be a problem. But it’s going to take a period of time, right? You first eat your meal.”

“Please send your request first, I can wait. I will not eat before I call my mother.”

The next morning, Chen Jianjun comes in with an exaggerated smile: “My superior has granted you permission to call your mother, but on two conditions: first, you cannot mention that you have been kidnapped or that you are under house arrest. You also may not say that you are in Xinyu. Second, the mobile phone must be held by us and you must use the speaker mode. Agreed?”

“I never had any intention of telling my mother what has happened to me. I just want to say hello to her and tell her not to worry about me.”

They call my mother’s phone and hold the mobile phone close to my ear. I hear my mother’s anxious voice: “Where are you? Why has your phone been off for so long? We were worried that something had happened to you.”

Calmly I lie to my mother: “I have been traveling in Europe. My phone broke. International roaming service is too expensive, so I cannot call you often. Please don’t worry. It’s much safer here in a foreign country than it is in China.”

In the past, whenever I traveled abroad, I have always called my mother before boarding my plane. Before I left Beijing, I used to email my younger brother my itinerary, contact numbers, hotel addresses, all kinds of information regarding accident insurances, and the names and email addresses of the insurance companies. This time is different. I don’t know whether or not my mother believes me.

After that I am allowed to call my mother once a week to say hello. In order to keep in touch with my mother, I take no chances by revealing my real situation to her.

The sleepless night is so long, I try to fill it with my thoughts. The feelings brought on by my thoughts can be warm and sad at the same time.

Ten years ago at a Christmas party in a bar in Sanlitun, Beijing, I met Xu Zhiyong, a Ph.D. student at Beijing University. That night, a group of his friends and their friends were enjoying themselves heartily. Against the noisy and chaotic backdrop, I had a quiet conversation with Zhiyong. He talked about his ideals of a constitutional government and the villages he regularly visited to conduct field research on grassroots-level elections. These topics deeply interested me, because his ideas were the same as my own. Ten years later, he became my lawyer in my lawsuit for freedom of speech and gave me tremendous help.

I came to know Teng Biao at a legal aid conference. When Zhiyong mentioned my lawsuit to him, he said without any hesitation: “Great. I support you!” The next time I saw him was in front of the Daxin Court House where people were showing support to Zhao Lianhai.12 Facing officers in plainclothes who were videotaping us, he shouted out: “This is Teng Biao! Do you dare to say your name?” All the women there adored him.

For the past year or so, I have participated in or filmed many citizen actions and legal cases that were initiated, sponsored, or supported by Gongmeng.13 They cover issues such as forced demolitions and relocation, educational equality, the Day of Twitter Friends on the Fourth of July,14 the Zhao Lianhai case, the Three Netizens case15 in Fujian, the Xia Junfeng case,16 the Leng Guoquan case,17 and many others. Shared ideals and common actions have created a strong bond among us. In my heart, Zhiyong and Teng Biao are not only my comrades, but also my brothers.

Early last year, I was harassed by Domestic Security for publishing my article, “In Search of China’s Path.” I called Auntie Qing, the wife of Tan Zuoren18 and a friend of many years, to express my sense of desperation and helplessness. Auntie Qing said: “You need a lawyer. Go to Pu Zhiqiang.” So I called Zhiqiang and we had our first meeting half an hour later in his very messy office. In front of him, I felt that I wasn’t at all like someone who was law-trained but a babbling seeker of help.

He interrupted me: “This is nothing, you will be fine.”

“If I am in trouble, will you agree to be my lawyer?”

“I agree.”

From then on, whenever I got into trouble, I went to him, still babbling as before, and I often depleted his patience. From his facial expressions I could read explicitly: I am that child who cries wolf. On October 24, he and I parted in Yichun. I went to Dandong to meet Teng Biao. During those few days, he always ended his phone calls or text messages with the words “Take care!” Now I suddenly realize: he was sending me warning signals. At this moment, what saddens me is that, in this land, the only thing my lawyer can do for me is to warn me.

The first time I heard the name Cui Weiping19 was through the poet Hai Zi.20 At the time, I was preparing to make a biographical film on Hai Zi. While researching, I encountered a series of articles written by Cui Weiping on Hai Zi. Upon first reading them I was very moved by her writings. Since then, I read all the articles by her that I could find. Later I met her at a farewell dinner for Tu Fu21 in Fuzhou. That was the prelude to the April 16th Incident.22 Tu Fu was taking a great risk going to Fuzhou to show support to the three netizens who were about to be tried. Teacher Cui openly joined the “Watch Group” to show her support. She said: “Today, let us forget about the world. At this moment, we only care about Tu Fu!” Several days later she wrote a long poem, “These Righteous People!” in which one paragraph is about me.

Along with the stream of my recollections there is also Older Sister Wang Lihong,23 Tu Fu, Tiantian,24 Wang Yi,25 Zhang Hui,26 A’er,27 Qiangben,28 and others.

Every time when I think of them, I feel a warm stream flowing down my cheeks. That excitement from my heart silently blends into the dark night and greets the dawn.

On November 14, I return to my room after dinner. I sit on my bed reading. I hear a knocking on the door. I don’t pay attention, believing it to be the bodyguards next door. Ms. Ouyang from Domestic Security answers the door. I hear someone say: “We’re looking for Hua Ze.” Ms. Ouyang slams the door shut. I understand what is going on. I can hear the loud calls from the outside: “Hua Ze, Hua Ze, please answer! Let us know whether you are inside.” I get up quickly from my bed, while Ms. Ouyang stares blankly at me. The voices outside become even louder: “Hua Ze, we love you!” My tears burst out. I rush to the door with no fear. Since Ms. Ouyang is guarding the door, I can only open the door a crack. But I can see three strangers’ faces: one woman and two men.

“I am Hua Ze. Who are you?”

“We are netizens, here to see you.”

“Where are you from?”

“They are from Xinyu. I am Chen Maosheng from Fengxin, do you still remember me?”

“Of course.”

We had communicated on Twitter. I remember his head shot – a handsome young man. He looks even more refined in person than he does in pictures. I shake hand with each of them and feel indescribable warmth. The female netizen hands me a bouquet of fresh flowers. They all tell me to take good care of myself. Ms. Ouyang pushes the door from behind and shuts it with force.

The room falls into dead silence. As she is changing her clothes, Ms. Ouyang tells me: “Two of them are from Xinyu Steel Mill, so-called rights defenders. They are bad, always looking for an opportunity to provoke people to make trouble for the government. …” I am not sure what she is talking about but I feel happy that Ms. Ouyang recognizes them, so they must recognize her too. They will soon spread word about me on Twitter. I will not disappear from this world without anyone knowing.

Ms. Ouyang finishes changing her clothes and hurries out. She is going to report this to her superior, leaving me to the other bodyguard. This is serious – I have been exposed. This will certainly keep them busy for a while.

The next early morning, Captain Hu comes and orders me to pack up and move.

I am moved to The New Blue Sky Business Hotel, not far away from the old one. This hotel has no courtyard and exits right onto a street. So I have to go outside of the hotel if I take my walk. Actually they had already allowed me to take my walk beyond the gate previously.

The new hotel has no dining service, so we have to go to a restaurant next door for meals. Each meal, we either spend above the limit or eat poorly. The rooms have no heating either. We stay here for about ten days, and I have no problem. But the bodyguards cannot stand the cold. They soon realize that the netizens were just visiting me and have no plans to rescue me. On the 11th day, we move back to the Xiaofang Guesthouse on the insistence of the bodyguards.

One night, not long after moving back to the Xiaogang Guesthouse, I have a dream. On a cold winter morning I was on top of Emei Mountain; snow was drifting down slowly; and the peaks near and far were covered in white. Morning bells rang from a monastery at the foot of the mountain, the sound rising up to the top in waves. This is a real scene from the Spring Festival of 1994, during my first trip to Sichuan, where I met Tan Zuoren and his wife. Sixteen years later the same scene comes into my dream. But now my life has been completely changed by the sentencing of Uncle Tan.29

Around the end of November, I hear that my house arrest may last beyond the Spring Festival of 2011, or even worse, according to some people, indefinitely. Since I know I was kidnapped and put under house arrest in connection with Liu Xiaobo’s being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, I have been psychologically prepared for the worst-case scenario of being released after December 10, when the Nobel Prize award ceremony is held. If that is not the case, I will go on hunger strike and protest with my death. I must somehow send a message to the outside.

I normally write in my diary daily. It is filled with scribbles and does not have complete paragraphs. It consists of disconnected phrases, to remind me of important events and how I felt about them. Because I know Ms. Ouyang often peeks into my diary when I leave the room, I would make a mark in my diary, such as putting it in a particular position, or leaving a strand of hair in it. So, sending a message out has to be done very carefully; she must not find out.

This note is written one evening while I hide myself in the toilet; the general idea is: “I am under house arrest and cannot contact my family. Please help me send a text message to the following two numbers: 186 … and 139 … (these numbers belong to Teng Biao and Pu Zhiqiang, which I had memorized on the train and would never forget in my whole life). The following are the contents of the text messages: 1) My mobile phone has been confiscated and I am asking for help from a stranger to send this text message, so please do not publicize it. 2) If I am still not released after the day of the award ceremony, I will go on hunger strike. Please think of a way to rescue me. 3) If possible (as I am concerned that their freedom may also be restricted), I authorize you two to be my lawyers. I have an authorization letter for Pu Zhiqiang at home (the exact location of the letter, and the contact information of the person who has my house keys, etc.). 4) I am in the hands of the Xinyu Domestic Security detachment, being kept in Room 9207 at the Xiaofang Guesthouse in Xinyu.” I put this note together with a fifty yuan bill in a pocket of my under shirt.

In the evening of December 1, when I take my walk outside, I stuff my note and the money into the hand of a stranger I have chosen beforehand (I am afraid I cannot give more details). I don’t know whether this stranger would send out the text message for me. But that is all I can do; I leave everything else to fate.

Two days later when I take my walk outside again, I see the stranger. He is actually waiting there, and he gestures OK to me.

As the day of the Nobel award ceremony approaches, I become more and more anxious. Every day without freedom is as long as a year. I feel I am entering a boundless dark tunnel. I know there will be light ahead, but I still cannot see it.

Many nights I am tormented by heart palpitations, which always hit me as I am about to fall asleep. The anxiety is beyond words; my limbs become weak, and I feel like screaming. I have to do my utmost to control myself in order to not go crazy. Facing this strong sense of helplessness, I keep telling myself: “You cannot have a breakdown! You cannot have a breakdown!”

Even if I am released the day after the Nobel award ceremony, I will have been cut off from the rest of the world for a full 45 days. For me, someone who values liberty over life, this is too great a price. Sometimes I wonder, if I had not been so unyielding after I was kidnapped and told them whatever they asked, they might have already released me or just restricted my movement, and not cut me off from the rest of the world. This might have been entirely possible. But I do not regret what I have done. From the moment they used violence to kidnap me, they foreclosed any possibility of negotiating with me. Not because I cannot compromise, but because I cannot yield to violence.

Nobody may blackmail me – not with violence, interest, or even familial love. Don’t mistake fragility for powerlessness, and don’t think that the insignificant ones have no dignity. What differentiates the strong from the weak is not the intensity of their power; rather, it is the firmness of their belief.

Finally the day of the Nobel award ceremony has come. Based on the time of day when the announcement was made, the award ceremony should be around five o’clock in the afternoon, Beijing time. Based on what has happened to me, I expect that everyone who could possibly go to Norway is being restricted. Therefore, no one from China can attend the ceremony. I hope there are rows and rows of empty chairs both on the podium and below the podium for the honored guests, and the camera slowly zooms in on these empty chairs. There is no better illustration of the current human rights in China than this, and this also shows the great significance in awarding this prize to Liu Xiaobo. When I think of that scene, I start to cry. (Not long after I was released, I saw the video of the ceremony. There was really an empty chair in the scene!)

On the morning of December 21, I announce my hunger strike!

That afternoon, Director Zhang of the Xinyu Public Security Bureau comes. He tells me that the day before he personally reported to the Jiangxi Provincial Public Security Bureau and he will receive instructions in a day or two. He wants me to be more patient. He also asks whether I have any requests. I tell him: First, tell me the reason for my continued house arrest; second, tell me when my house arrest will end.

I lie on the bed, resigned to my fate and letting my consciousness fade away. My body is floating, weightless, as if it is another me; no, it is my soul that has left my body and is looking down from midair:

“How long can you keep this up?”

I smile back: “To the extent of the challenge.”

“Do you want to destroy yourself?”

“No. This is precisely what will make me perfect. They want to use coarseness, wickedness, and emptiness to destroy me. I will resist with fineness, purity, and vitality. They can destroy my body, but never my heart.”

On December 15, Captain Hu replies to my requests: “First, there will be a concert the day after the award ceremony. Moreover, many rights defenders have gone to Beijing, and the Beijing police are overwhelmed. Therefore, we cannot release you yet. Second, we will definitely release you before December 20. The condition is that you must eat.”

That day, I end my hunger strike.

In the evening of December 17, Captain Hu comes again: “I have some good news. You will be freed on December 20th. Where do you want to go?”

“I want go back to Beijing.”

“How?”

“Either by train or by airplane.”

“You can ask Chen Ming to buy a ticket for you.”

“I am not here for vacation, or to visit my family. How you have brought me here is how you will send me back. I don’t have any money on me. If you don’t send me back, I will wait for my friends in Beijing to come get me.”

“Wait, I will ask for instructions from above.”

The following day, I get a reply: We have bought a sleeping berth ticket for you on the train on December 20; we will take you to the train.

Freedom! Freedom?

On the morning of December 19, Captain Hu tells me to pack my things and leave the hotel. He says that he could not get a ticket for a sleeping berth on the train to Beijing and has asked the Fengyi County Public Security Bureau to make arrangements. “Today we go to Fengyi first, and tomorrow afternoon we will see you to the train.”

I start feeling uneasy, because what he says does not sound logical. Xinyu is a city directly administered by the provincial government, and Fengyi is a county administered by Xinyu. A municipal bureau can’t even get a train ticket and needs a county bureau to make arrangements?

Fengyi is only thirty some kilometers from Xinyu, and it takes half an hour to get there. We are in two cars going through the central area of the county and heading toward the suburbs. The farther we go, the more deserted it gets. Finally we stop at a holiday resort at the foot of a mountain. The police officers from the Fengyi Public Security Bureau are waiting for us. We are the only group staying at the resort. Probably because we are in the mountains, it is very cold, and the temperature is at least three degrees Celsius lower than in the city. The entire night I wrap myself tightly with a comforter, my thoughts running wild. Will they send me to a Reeducation-Through-Labor camp? Will they formally arrest me? In May of this year, a friend of mine was arrested in Jiangxi for “inciting subversion.” After he was released on bail he told me that the Jiangxi police asked him for information about me.

A bodyguard is playing with her computer next to me. I ask her to look up the arrival and departure schedule for the next day’s Fengyi-Beijing train. She checks it on Baidu.com and is startled: “The train to Beijing does not stop at Fengyi.”

I start to throw a tantrum: “Go ask your leader: where is he sending me?” This bodyguard is a young and simple girl. She says, “The order I received is that our assignment will be over tomorrow afternoon. You will be released for sure tomorrow. Don’t worry! The leader will arrange things well.”

A moment later, Director Zhang of the Xinyu Public Security Bureau calls and says that he will come to see me, and asks for directions. Someone in the Fengyi county bureau goes in a car to pick him up. After a long time, another bodyguard comes and tells me that the director did not come: “He will come tomorrow morning for sure. The director says he will see you off.” I feel the situation is getting more strange.

A sleepless night. After I get up in the next morning, I do not say hello to the bodyguards; I open the door myself and walk straight out, and sit down in the yard to get some sun. I feel extremely disturbed, and I cannot figure things out. If they are going to release me, why bring me here? Several bodyguards come out to me and start assuring me: “There won’t be problems. The leader will arrange things well for sure. If you are not released today, we will go on a hunger strike together with you.”

Almost noontime, we finally leave, heading to an upscale restaurant in Fengyi county. A whole group of people is waiting for us at a table. They include Director Zhang, Captain Hu, and four people from the provincial Public Security Bureau. Among them, an older person who looks like a leader says: “We came here to take you to Nanchang, where you will fly back to Beijing.”

“When will you give me back my mobile phone? I need to call my friends to pick me up at the airport.”

“Don’t worry. We will give it back to you.”

I am in no mood to eat. Isn’t Xinyu closer than Nanchang? Why go there via Fengyi?

Among the four from the provincial Bureau is a middle-aged woman, Ms. Xiong (she didn’t introduce herself though), who is so polite that I cannot think of her as a Domestic Security officer. She says: “Teacher Hua, you see big changes in Jiangxi, right? Please help us spread the word.”

“I am not a publicist, I only do criticism.”

“Teacher Hua, don’t you make historical and cultural documentaries? Our Jiangxi has a long and rich history.”

“That’s true. I once did some research on classical academies in Jiangxi. Unfortunately, the department that I belonged to at the time did not think this program would get good ratings, so it was not approved.”

“Fine, then. If you propose it to us, we will help you plan it. We can provide funding, facilities, and all the amenities.”

“Ha ha ha ha … that’s good.”

This is fascinating. It does not look as if I am going to be sent to a Reeducation-Through-Labor camp; it looks more like amnesty.

After lunch, I get in a Ford minivan with the four from the provincial bureau and a female bodyguard. Behind us is a car driven by Chen Jianjun, the Domestic Security officer from Xinyu. We drive as if in a parade toward Nanchang.

As we are approaching Nanchang, the older provincial official says, “We still have several hours before the flight departure; let’s accompany Teacher Hua to visit the Tengwang Tower.”

In a Teahouse at the Tengwang Tower, they conduct a carefully pre-arranged “friendly conversation” with me:

“Teacher Hua, you have been in Jiangxi for almost two months. Have the comrades in Xinyu taken good care of you?”

“Very good. Sorry for troubling all of you.”

“You have a law background. So do I. Let’s put aside the legal issues. Some things have to be left for history to judge. Do you agree?”

I do not say a word, keeping a smile.

“Today I am not talking to you in any capacity, just as someone a few years your senior. Will you listen to a word of advice?”

“Please, go ahead.”

“From now on, don’t get involved in matters related to Liu Xiaobo.”

“What kind of Liu Xiaobo matters?”

“Such as the signature campaign.”

“That sort of thing doesn’t happen very often.”

“Good, that’s good. Also, as for matters related to the Jiangxi police, you don’t need to mention them.”

“I think the Jiangxi police have done well, enforcing law in a civilized way.”

“From now on, we are friends. If you have any business in Jiangxi, feel free to contact us. We will do our best to help. You and our Little Xiong can exchange phone numbers, so we can keep in touch. We welcome you to return often, but, of course, not in this way.”

I am wondering, so Little Xiong is going to be my special agent? I answer: “I will come back often; I still have family here. But it is beyond my control whether I will come back this way.”

“Your project on Jiangxi classical academies is a very good idea. You can send us a proposal; we can get it started immediately. There should be no problem.”

“Good, I’ll contact you when I need to.”

“Then it’s settled.”

At seven o’clock in the evening, I am taken to the VIP waiting area. Little Xiong asks me for my National ID to get the boarding pass. I once again ask her to return my mobile phone. Xiao Xiong says: “We will put it in your checked luggage.”

I become serious: “The mobile phone is a valuable item and should not be checked. You must give to me. It will be late when I arrive in Beijing; I am only wearing a thin layer of clothing, so I have to call my friend to pick me up.”

“I have prepared extra clothes for you. I know you don’t have enough money on you, so I have also provided taxi fare. In addition, our Bureau has prepared some gifts for you, so I will pack them together with your phone and check them.”

“Are you worried that I will call my friends in Beijing, and a welcoming party will meet me at the airport? It is so cold and it will be very late when I arrive in Beijing. I won’t make many people come meet me, I promise.”

“It’s better to check it.”

“I don’t promise anything that I am not able to promise. Once I have promised, I will keep my word. Please give me back my mobile phone.”

The older person intervened: “Okay, give it back to Teacher Hua. Since Teacher Hua has already been so clear, I also want to tell you: We are indeed concerned about any new snafus. We are also looking out for you and wish you a safe journey home.”

The airplane takes off at eight o’clock. At 7:40 p.m., I am escorted directly from the VIP waiting area to the airplane. At the gate, I wave to the people from the provincial bureau and enter the airplane. I immediately turn on my phone and call Teng Biao to tell him I am safe.

At this moment, I finally feel that I am truly free!

The day after I returned to Beijing, I find out why the last two days before my release the Jiangxi police went through so much trouble to transport me from one place to another. On December 18, Teng Biao, Xu Zhiyong, Tu Fu, and some other friends organized a “Fragrant Soul Watch Group.” The group’s members from different parts of China, including four lawyers, had decided to go to Xinyu to rescue me.

When the bell rings in the New Year, eleven days after I regained my freedom, I write down the following words: I have a dream. I dream that in the near future my friends will never be kidnapped, disappeared, or imprisoned. I dream they will never live in exile as sojourners far away from their homes and country.

Translated by Ming Xia. (The translator wishes to acknowledge the contributions from Alex Feng and Julia Xia.) Translation edited by Human Rights in China.

The Ordeal of a Fragrant Soul

1-1024x768.jpg)

1-1024x768.jpg)

近期评论